We Are Not Immune: Stress and Autoimmune Conditions

It is often said we take our health for granted, but the reality is that it is our underlying immune system that is the forgotten hero. It is our immune system that is challenged the most in times of stress, particularly chronic stress. Chronic stress is apparent after large scale disasters such as cyclones, hurricanes, floods, and fires. Chronic stress and its effect on health is the price paid by our broader population, well after the cleanup.

I was developing and writing a new course about immunity over Christmas, however, I found it difficult to write as I was drawn to the images of the Australian bushfires. The distress and destruction drew me back to the floods of 2011 in my own city of Brisbane. The floods were devastating, not only on the property but also on the health of people within the affected communities. Our studios were in the epicenter of the flood-affected communities of Brisbane and about 6 -7 months after the floods we started to see more and more clients affected by autoimmune flare-ups and severe illnesses. On top of recent natural disasters we now have coronavirus being a major concern in China and globally, creating more stress and anxiety in individuals and in society generally.

In this article we will talk briefly about:

- the immune system

- the autonomic nervous system (ANS)

- some ideas about managing the ANS

What are the elements of our immune system?

The immune system has two components:

innate immunity – this includes non-specific things like your skin and mucus production. Innate immunity also includes inflammatory responses which create antigen-presenting cells that are used by adaptive immunity.

We have particular cells of our innate system called natural killer cells. These cells are part of our white blood cells. These natural killer cells generally detect and destroy cell mutations and tumors. The chemical response of stress discussed below is known to affect and destroy these natural killer cells.

adaptive immunity (also known as complementary immunity) – you acquire this as a result of immune challenges experienced by the innate immune system.

Adaptive immunity is acquired through exposure to viruses and bacteria, particularly when we are younger. The thymus is a gland behind the sternum and is responsible for the production of our T cells. A T cell is a type of white blood cell that defends the body from viruses and infections. The thymus starts to shrink in our late teens and early 20s, after that age we have an immune memory in our body's innate immune system.

This is the reason why new viruses such as the coronavirus can be so challenging for populations. Essentially, we have not been inoculated (vaccinated) against that virus through previous exposure. Our bodies do not have specialized memory T and B cells in order to defend against that virus. Please remember this is a very simple explanation and we could spend weeks going through the subtleties of the immune system.

What is stress?

Stress is how the brain and body react to a stimulus or demand. Stress can trigger a variety of physical and/or mental responses. The effects of stress can also be discriminatory, effecting us greater if we have lower socioeconomic status or if we have less control over our lives. These are the findings that came out of the famous Marmot study into Whitehall.

What I like about this study is that it highlights how important it is to be supportive of people and to create opportunities for our colleagues and clients, which allows them to feel a sense of control. Creating these opportunities for success and control is part of how we can manage our stress and also its resultant impact on our body’s immunity.

If you are interested in the topic you can watch this PBS video documentary, which is about one-hour long Stress, Portrait of a Killer – Full Documentary (2008).

How does stress relate to our immune system?

When we experience stress, parts of our innate system (such as the TH cells) are undermined by the glucocorticoids (steroids) produced by the stress response. This results in a cascade of events that can lead to the immune system going haywire, with the potential development of autoimmune conditions and cell mutations that lead to some types of cancers.

The cascade and some types of autoimmune diseases and how to handle them in a movement studio setting will be covered in greater detail in the Claiming Immunity course.

What is the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) and how does it relate to immunity?

The ANS is associated with the flight and fight response, though it is more than just that. We need a little bit of stress to get us moving and to get us out and about – this is essentially what happens through the somatic nervous system. However, imbalances in our ANS can lead to all sorts of health problems. Once again this is an area of health and wellbeing that is only just being understood.

The ANS has two components – the sympathetic and the parasympathetic system – which work together to regulate our:

- heart rate

- blood pressure

- digestive systems

- bowel and bladder

- breath

When we are stressed the sympathetic system steps up and:

- increases our heart rate

- increases the blood flow to our periphery – we need blood there to run away in case of danger, and this means increased pumping of the heart.

- decreases digestion and absorption of food and nutrients – these are put on hold

- increases our breath rate, though breaths become more shallow

The consequence of all this means that our body is not eliminating “fluids” which include inflammatory markers. As the inflammation builds up it starts to damage parts of our innate immune system, making us more vulnerable to illness and autoimmune conditions.

For those interested in the ANS including some of its functions and how to work with it, the Introduction to Neuroanatomy (online course) covers this system in more detail.

What are some ideas about managing the stress response and assisting in immunity?

Breath is a key component for handling the immune system and its associated fluids. I understand this is a double blow for those recently impacted by the bushfires because they could not breathe deeply and properly from all of the smoke. Once the smoke has cleared, it is essential for people in these communities to achieve deep diaphragmatic breath with a focus on the inhale.

The inhale breath is important for a number of reasons, as detailed below.

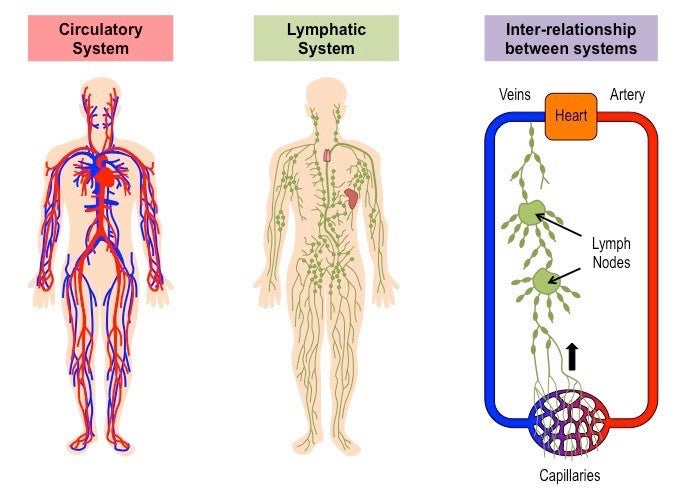

It creates a vacuum by increasing the volume of the lungs and thoracic spine, in turn creating a low-pressure system in the thoracic cavity. This low pressure encourages fluids (think the lymphatic fluids of our immune system) to return into the venous system and back to the heart. This venous return encourages the recycling and elimination of the fluids of inflammation so that they do not build up and cause problems.

The diaphragm sits above the cisterna chyli, an important node of the lymphatic system, which also plays a role in lipid digestion. The movement of the diaphragm helps facilitate the movement of the lymph through this important node, once again encouraging the recycling and elimination of the fluids of inflammation.

Lymphatic and circulatory systems

Movement is also important as it activates what is known as the muscle pump (the skeletal muscles that helps the heart in the circulation of blood). The muscle pump helps to move fluid from the lower extremities, where it can be difficult to achieve venous return back to the heart. When we are wanting to help people clear the fluid in the immune system we start proximally and then move distally. We have discussed these principles in earlier blogs and they can be considered relevant for working with people who may be suffering from stress.

Some movement and studio strategies include:

- focus on inhale breath patterns to help with fluid return

- time long deep exhale breaths in order to maintain the calming of the ANS (these breaths should be long and slow, controlling the diaphragm to allow it to fully ascend on the exhale – examples are seen in the videos at the end of this article)

- encourage thoracic mobility early in the session

- encourage calf muscle contraction and combine that with inhales

- create flow and encourage sensory modulation practices in your own studio session (this is a whole article in itself and is part of the lecture series we are doing for the APMA conference in Melbourne 2020

- mental health issues are part of our health story, and when you or a client need help remember places like Lifeline.

- reduce infections and the spread of infections in your studio space. Infections are particularly problematic when people have cuts or grazes that mean their innate immune system is compromised. Some recent innovations for studios to keep their studios clean and a bit stylish include the bring your own straps idea, which can be purchased through ELEMENTS by Momentum World and Good Citizens LA. Then there are things like good quality cleaning products and clients using some of the specialist Reformer towels.

- be kind – ditch the go hard or go home attitude, and encourage a more equal relationship between practitioner and client. Remember your client is the expert in their own body. As a practitioner, you are facilitating their expertise, not imposing your opinions and systems on to them.

- listen – stress and distress experienced by others can be helped, even in a small way, by being listened to and assisted as able.

As humans, we are generally kind and we do step up and help others. We saw this across Australia as part of the bushfire response, and also after floods and cyclones.

Below are some video ideas for exercises or strategies that can be used in a studio setting. The first video is from the Movement Matters videos in the Introduction to Neuroanatomy (online course) and is very relevant to this topic.

To learn more about any of our courses you can go to Body Organics where we list all of our courses, books, and products.

Bibliography

BONE MARROW, THYMUS AND BLOOD: CHANGES ACROSS THE LIFESPAN. (2009). Aging Health, 5(3), 385–393. doi:10.2217/ahe.09.31

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!

You need to be a subscriber to post a comment.

Please Log In or Create an Account to start your free trial.