Pilates and Yoga: Better Together?

Although Pilates and Yoga have their differences (as their dedicated practitioners are quick to point out), the two practices confer many of the same benefits, from relieving back pain to improving focus.

I recently spoke with Gia Calhoun and Alana Mitnick, content heads for PilatesAnytime and YogaAnytime, respectively, about what makes these two related disciplines unique as well as similar. (The two sites share a parent company as well as a studio for filming classes.) Read on to discover how adding Pilates to your yoga practice, or yoga to your Pilates practice, can improve your fitness level, boost your reserves of calm, and prevent overuse injuries.

Yoga and Pilates are accessible movement practices that prioritize mind-body connection. Moving dynamically through sequences of exercises or postures helps us tune out chaos and develop greater focus. Both styles of movement offer modifications, meaning that they are appropriate for students of all levels and abilities. Even some of the shapes are similar, such as the V-shaped Teaser that resembles Navasana, or boat pose, or Rocking, which takes its inspiration from Dhanurasana (Bow Pose). So, pretty similar, right? Not so fast. It’s important to note that these two systems have completely different histories and lineages.

Yoga originated thousands of years ago in India and is rooted in ancient Indian philosophy and culture. TKV Krishnamacharya taught and promoted yoga asana in the 1900s thanks to the patronage of the Maharaja of Mysore which enabled him to popularize yoga throughout India. His pupils BKS Iyengar and Sri K Patthabi Jois went on to spread yoga in the Global West through the lineages of Iyengar Yoga (heavily alignment based, uses a lot of props), and Ashtanga Yoga (a set sequence of poses heavy on sun salutations that emphasizes moving dynamically on the breath and is akin to what’s labeled as ‘Vinyasa Yoga’ in many studios now). Other important teachers and lineages include Kundalini, Yin, and Bhakti yoga.

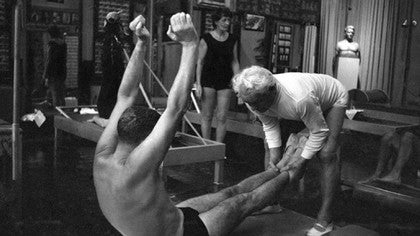

A contemporary of Krishnamacharya, German-born Joseph Pilates (1883-1967) spent World War I in an internment camp on the Isle of Man, where he had the opportunity to teach what would become the Pilates Method to his fellow prisoners of war. Pilates had a sickly childhood, followed by an intensely physical career, with stints as a boxer and circus performer. These diverse life experiences inspired his passionate understanding of body mechanics, breath, and movement. During World War I, his work with injured combat veterans sparked his interest in movement for rehabilitation that closely overlapped with modern physical therapy. Pilates moved to New York City in the early 1920’s, established a studio, and became sought out by the dance community as well as socialites and businessmen. His techniques, which drew from varied sources including physical fitness and yoga, grew in popularity. A handful of teachers who studied closely with him went on to develop their own lineages of teachers, very much like what happened with yoga in India and beyond.

As practiced in the modern studio setting, yoga and Pilates have evolved to be more connected and even interchangeable to the general public. Common misconceptions about both include the following: that they are only pursued by women and dancers, that they require a baseline level of fitness or flexibility to participate, and that they prioritize flexibility over strength or endurance. As a physical practice, Pilates now mirrors what Yoga has become for many: a workout performed on a mat (or, in the case of Pilates, on specially designed apparatuses) with special attention paid to alignment, breathing, and technique.

“Pilates meets you where you are and it gives you what you need,” says Calhoun. “If you need more strength training, you work on that. If you need more flexibility training, you work on that. For an instructor, Pilates is about teaching the body in front of you, and finding modifications if necessary. As a practitioner, it’s about moving your body with intention and attention. There is a reason and specific alignment for every exercise.”

Yogis who add Pilates to their movement mix will benefit from a stronger “Powerhouse” region, also known as the core, the area from which all Pilates movement originates. A strong core can help with balance, important for inversions or arm balances, and help protect the lower back during backbending sequences. Because Pilates is known for working the small, supporting muscles, it can shore up the shoulder and hip girdle, protecting these Most Valuable Player muscles from overuse injuries. Pilates apparatuses like the Cadillac and Reformer provide support and feedback to the body in a range of positions, including kneeling, standing, and lying down, and this can foster confidence and body awareness that transfers to the yoga mat where there is no equipment involved (other than a few small props).

“Yoga brings us into a more intimate experience with ourselves,” says Mitnick. Just as Calhoun did when talking about Pilates, Mitnick emphasizes the importance of modifications to tailor the practice to the individual student’s needs or abilities.

Mitnick and Calhoun agree that as a general rule, people looking for spiritual growth and understanding often are drawn to yoga, while people looking to rehabilitate after an injury often gravitate to Pilates. But there are examples of yoga being used to heal injuries, and of Type A Pilates practitioners experiencing deep transformative shifts in their mental health because of their Pilates practice.

“Yoga gives permission to be yourself, permission to listen to your body and the inner guidance coming through you. The deeper practice of yoga really happens off the mat,” says Mitnick. “Every interaction and act is a practice of yoga. Part of the process in yoga is to see more clearly, having moments of insights and emotion so that we can begin to connect to a more quiet place within ourselves. It's an ongoing process of self-awareness to reduce suffering.”

Pilates tends to attract a lot of perfectionists, so the emphasis on what takes place outside the studio can be novel. As Calhoun says, “Pilates tends to be more about precision. Students might get more permission to explore from yoga. The internal, psycho-emotional aspect of yoga is a nice counterpart to the emphasis on the physical in Pilates.”

A Pilates practitioner who adds yoga to his or her wellness routine will get to experience stillness during long holds or seated meditation, something that doesn’t happen a lot in a flowing Pilates session. There may be elements such as chanting or music that are not part of a traditional Pilates practice. And there’s thrill in learning a new set of postures and seeing how the fruits of a Pilates practice can support good yoga technique, from a supple spine to a strong center.

Perhaps Kira Sloane, president, YogaAnytime.com, put it best when she said, “The difference is that Pilates helps you keep it together and yoga helps you let it all fall apart.”

Have you discovered that your Pilates practice has transformed or benefited your yoga practice, or vice versa? Let us know how in the comments below.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first!

You need to be a subscriber to post a comment.

Please Log In or Create an Account to start your free trial.